Players encounter many types of maps in tabletop RPGs. There are maps for hex crawling, dungeon crawling, and navigating towns. There are maps for finding treasure and maps found as treasure. Maps found as treasure are especially common in Dungeon Crawl Classics funnels. For instance, players can find a treasure map in Harley Stroh’s Sailors on the Starless Sea; a building deed and map of the building’s location in Mark Bishop’s adventure, Nebin Pendlebrook’s Perilous Pantry; and more recently, a topographical map on a wrecked spaceship’s console in Michael Curtis’s Danger in the Air. Unlike other forms of treasure that players may find, such as swords, spells, or silver, which serve to strengthen the player, maps are useful because they give players a new lead to follow in subsequent sessions. Most modules offer little advice on how to integrate these maps into future adventures, however. In this post, I explain how I handle maps as treasure in a hexcrawl setting.

Currently, I am running a West Marches campaign that uses fog of war. If players want to know what is on a particular hex on the world map, they need to sally forth and see for themselves. Giving them a map as treasure invites them to continue exploring places they might not have otherwise attempted to traverse, such as miasmic marshes or perilous peaks. Alternatively, they might send a cartographer (the mechanics of which I noted in my last post) to reconnoiter.

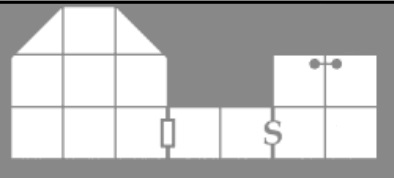

When players find a map in my game, I hand them one (and staple it to their character sheet). This map is comprised of a single hex flower with its roads, rivers, and terrain types identified and a compass rose to indicate which direction is north (figure 1). Sometimes I indicate landmarks (especially if they are looking for a specific building), but not always. It just depends on the situation. For instance, in Danger in the Air, Curtis explains that the map shows natural features like mountains, forests, and rivers, “but not roads, towns, or other constructed landmarks” (10). And so, in that instance, I omit them. The one detail I never share is where the flower is located on the hexmap. Players need to find it on their own.

Figure 1. The “X” marks the location of a building described on a newly acquired building deed. The pencil is a road.

When players believe they have found the location identified in the map fragment, they need to spend time searching the area to confirm their suspicions. Thus, even if they have previously revealed a section of hexmap indicated by their map fragment, they still need to travel to the specific location to confirm it. The length of time required to search an area varies based on what they are looking for. If players are looking for an obvious landmark, like an ancient wizard’s tower, they find it immediately. If they are trying to find a hidden cave entrance, fairy commune, or buried treasure, it may take days or weeks. Whenever players choose a wrong location to search, it should take longer than normal to conduct the search before they realize their mistake. After all, if players believe they have found the location, they will not be content to perform a simple search. They will leave no stone unturned.

Compared to other forms of treasure, maps encourage a more proactive playstyle since they give players an objective. Players need to remain alert for any landscapes that match the terrain on their map, otherwise the map will be useless. Most treasure items, such as potions or weapons, are reactive in nature; they only see use in response to a threat or opportunity. The reactive nature of some items often results in players never using them because they keep saving them for a greater threat that never materializes. I practically never used an escape rope in any Pokémon game for precisely this reason.

Overall, there are several benefits to providing players with maps as treasure. From a player’s perspective, a map is a promise of additional treasure. A map also gives players a destination to strive toward, regardless of whether they currently know its exact location. From a DM’s perspective, maps as treasure encourage players to explore the world more. Giving players maps on scraps of paper makes them more memorable as well. Players invariably forget to use certain items they acquire over the course of a campaign because they lose track of them on their character sheet. Tangible items, such as scraps of paper, are less likely to be forgotten.

And so, next time your players find a map, consider letting them roam the world looking for it. When it comes to maps as treasure, the real treasure is the journey, not the destination.

Coda: Applying This Technique in Other Settings

If you are running a hexcrawl in which players can see the world map from the start, my method may still be used—all you need to do is provide players with less information. For instance, instead of giving them a whole hex flower, give them three hexes.

Although I have yet to do so, this exploration mechanic could easily be transferred to dungeon crawls as well. For instance:

A dying dwarf explains that there is a sanctuary in a nearby dungeon with a hidden compartment under a magically-sealed flagstone. Anyone who lifts the flagstone will find thousands of gold and electrum pieces, as well as a legendary war hammer. There are a few other items, but the dying dwarf cannot remember what they were. Nor can he remember what floor the secret chamber was. The dwarf is certain, however, that the room was hidden in a secret passageway stemming from a 20’x20’ room containing nothing but a ladder (figure 2). He points directly at dwarves in the party, saying that anyone can find the room, but only they can unlock the treasures within.

Figure 2: A map leading to the dwarf’s treasure in Michael Curtis’s Stonehell Dungeon.