There is a lot of advice floating around the OSR-blogosphere on how to create rumors for your campaign. The Alexandrian’s three-part series on rumors (Rumor Tables, Hearing Rumors, and Restocking Your Rumor Table) offers one of the most exhaustive explanations.

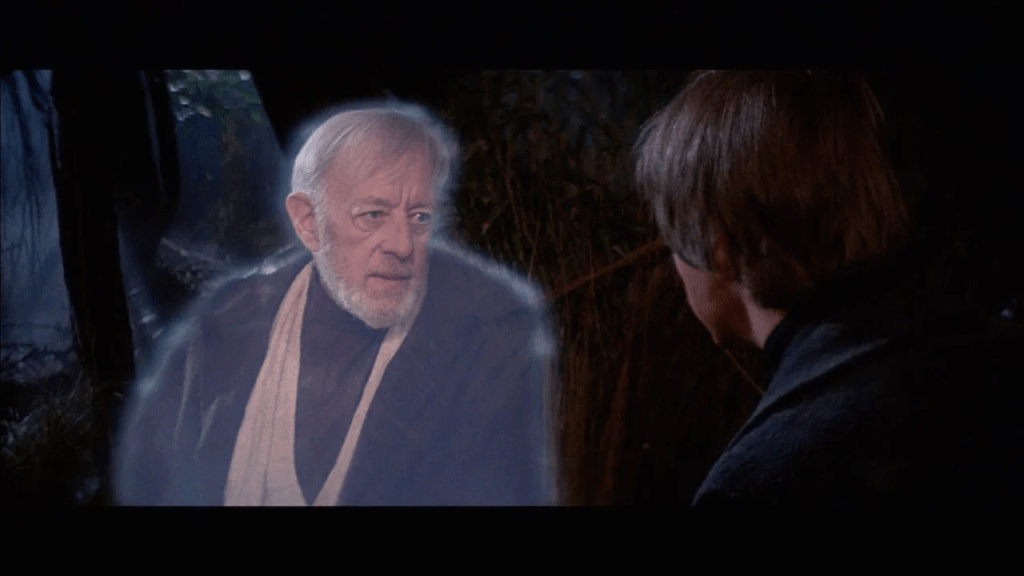

At their heart, rumors are just pieces of information that may or may not be true. Some are outright false, while others contain a mix of truth and error. Some may have been accurate once, but now they are outdated. Finally, as Obi-Wan admitted, some details are “true. . . from a certain point of view.”

Justin Alexander notes several different ways to deliver rumors to players. In my West Marches hexcrawl, I use a table with 20 rumors: 10 true, 6 partially true, and 4 false. (Players don’t know the ratio; I’m just sharing it to clarify my approach.) Between sessions, each player rolls a d20 and receives a rumor of uncertain accuracy. The group decides which rumor(s) to follow up on and I prepare the next session accordingly.

False and partially true rumors are the trickiest ones to handle. Players can end up on a wild goose-chase or never appreciate the nuance of a partially true rumor. For a real-world analogue, consider the oft-repeated claim that carrots are good for your eyes. While the vitamin A in carrots is good for your eyes, eating carrots does not dramatically improve your vision. This idea was propagandized by the British during World War II to mislead the Germans, who were wondering why so many of their planes were shot down at night. The truth was that the British were using a new technology: radar. I remember hearing this folk wisdom well into the 1990s. Even now, the number of health websites fact-checking this claim suggests that it is still alive and well. (Perhaps its longevity stems from the time-honored ritual of parents pleading with their children to eat their veggies, but I digress.)

Likewise, false or partially true rumors can persist in your game. Perhaps your players falsely believe that an object exists at a specific location, but they continue to search long beyond reason because they believe they just haven’t found it yet. Alternatively, they may find it, but because the rumor is partially true, they don’t appreciate which aspect of the rumor was true. Maybe the object exists, but it lacks the exact magical properties needed. (Similarly, it’s totally possible that the rumor is true, but despite your players’ best efforts, they never managed to find it located in a secret passage or hidden in a fountain and so they incorrectly write it off as a false rumor.) These results are not necessarily a problem, but if players feel like they are repeatedly hitting dead ends, their interest in rumors can plummet.

Investigating Rumors

While there is plenty of advice on how to create rumors, there is less advice on how players should go about investigating them. Unlike 5e, OSR games do not have insight, investigation, or perception checks. Instead, OSR game designers encourage player ingenuity and agency. While I prefer the OSR playstyle, I also think this framework often overlooks or downplays the extent to which player agency is learned. For instance, it’s commonly understood that iron pitons can be used to jam doors shut (or open), but I have never seen a new player arrive at this conclusion on their own. Put simply, sometimes players need to be shown how they could do something to give them more agency.

The following section is adapted from a handout I created for my players to help them figure out which rumors may be true or (partially) false. My campaign uses Dungeon Crawl Classics, but most of these options are transferable to other games. The point is not to eliminate all uncertainty, but to help players better understand their available options—and hopefully think of others.

Methods for Investigating Rumors

There are four primary methods for investigating rumors. Players may use any combination, but each attempt will take time and possibly resources.

- Consult the Rumor’s Source

Players may conduct a Luck check to locate and question the source. Success results in additional information. Failure means they cannot remember or find the rumor’s source.

This option is only available during the session in which the rumor is received. Each player may only make a Luck check for the rumor they heard (i.e., rolled for).

- Explore the Rumored Location

The party may visit the location to see firsthand whether the rumor is correct. As noted earlier, this method is not always reliable. In a hexcrawl, verifying a rumor through exploration can also take considerable time.

- Make Trained Skill Checks

Characters with a relevant profession may attempt to assess the rumor’s accuracy by conducting a trained skill check (d20 modified by intelligence). For instance, a smuggler, merchant, or outlaw could have insight into recent reports that “A shipment from the east was robbed. The robbers were cordial and did not kill anyone.” Does that rumor seem likely? Are such professionals aware of a specific band of thieves in that region? Alternatively, an elven artisan or glassblower may know something about a rumor that “A group of artisans have taken residence in Old Grunndale’s chancellery”—that, or they may know who to ask.

The difficulty of the skill check should depend on details like the obscurity of the subject, quality of available information, and/or how far removed the rumor is from the character’s area of expertise.

The party may also consult NPCs with relevant expertise, such as hirelings, but these trained skill checks are concealed by the DM. These checks generally require payment and/or favors from the party.

- Rely on Magic

Spell casters can investigate rumors in at least three ways:

- Elves and wizards can seek clarity from their patron, though these entities may demand a payment, favor, or task—if they choose to respond at all.

- Clerics may use the divine favors associated with deities like Malotoch and Shul to ask narrow questions.

- Spells like consult spirit, second sight, and speak with the dead allow casters to access knowledge beyond their own.

Coda: Player-Oriented Rumor Creation

Earlier this summer, a player asked me if they could spread a rumor of their own. I have never had a player ask me that before, but I loved the idea and encouraged them to do so. I let them know that I would perform a roll behind the scenes to determine its influence.

You might also consider explaining to players that they can circulate rumors of their own to help nudge the world a little. These rumors are usually meant to influence NPCs, but they could also target other players (or parties, if your world has multiple groups playing in it).

Players wishing to circulate a rumor need to explain:

- The rumor in a sentence or two.

- Whether it’s accurate, fabricated, or somewhere in between.

- How they are spreading it (e.g., tavern talk, speaking with the town gossip, paying a town crier, carving it into a dungeon wall).

The DM determines how far the rumor travels, how it’s interpreted by NPCs, and what consequences—if any—it may bring.

Leave a comment