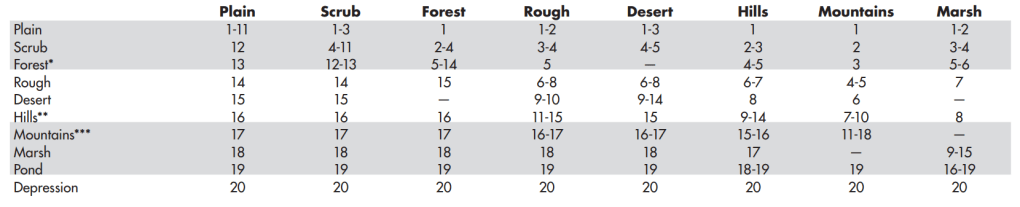

Over the past year, I’ve been inspired to try solo play after watching Daniel Norton’s solo campaign, which uses his homebrew Unchained. Initially, I tried to do everything identical to him as I gathered my bearings—this included purchasing a copy Outdoor Survival to use its map. In recent months, however, I’ve wanted to try running a solo adventure that follows the same format of the West Marches hexcrawl campaign I’m running for my friends. In this campaign, my players are exploring the world map with a fog of war mechanic. Until they travel to or chart a hex, they don’t know what’s in it. While it’s trivially easy to generate hexes on the fly using procedural generators, such as Appendix B: Random Wilderness Terrain from AD&D’s Dungeon Masters Guide (fig. 1), I’ve struggled with generating roads.

Fig. 1. Appendix B: Random Wilderness Terrain

Unlike terrain, roads need to be intentional. Roads are built by individuals to facilitate the movement of people and/or goods. As such, roads must link communities together and offer destinations.

There are several ways to get around this procedural generation problem. One can sketch roads on a blank hexmap at the start and then generate terrain as the party explores the hexmap. Alternatively, one can generate all the terrain at the start and then place roads based on what makes sense—this is what I did for my current hexcrawl campaign since I wanted to finetune my world before my players interacted with it. But again, since I want to be surprised as to what exists in my world, neither of these approaches really work for my solo campaign ambitions.

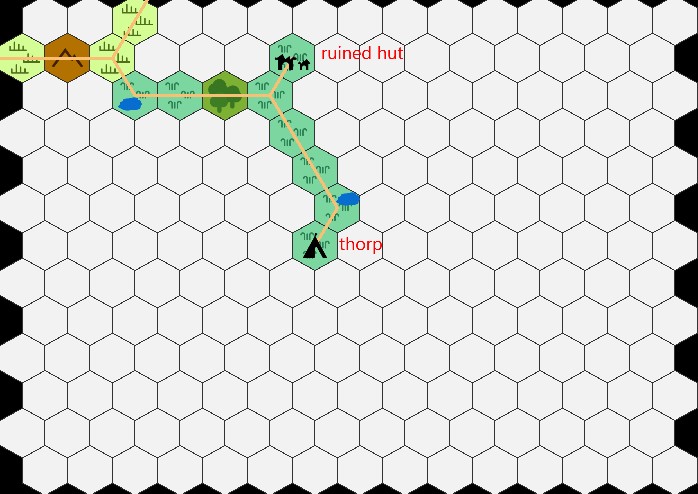

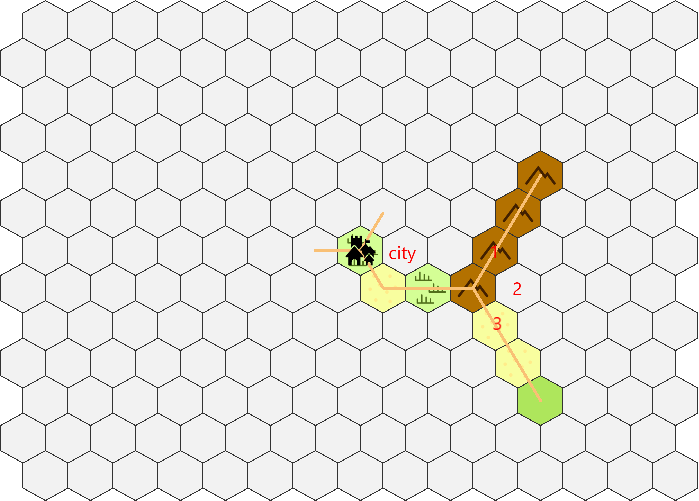

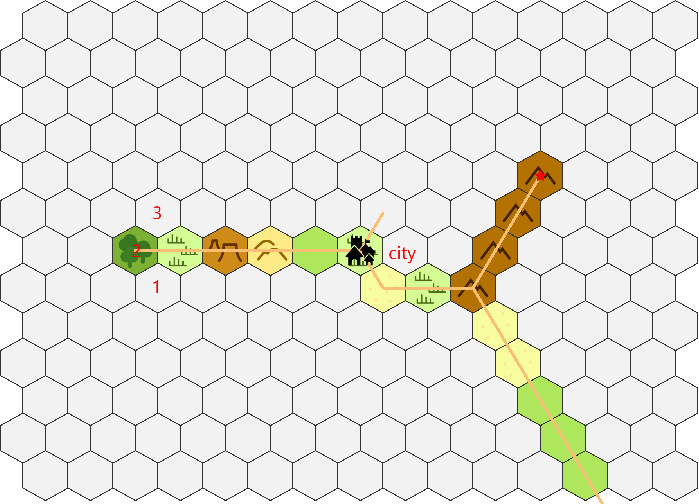

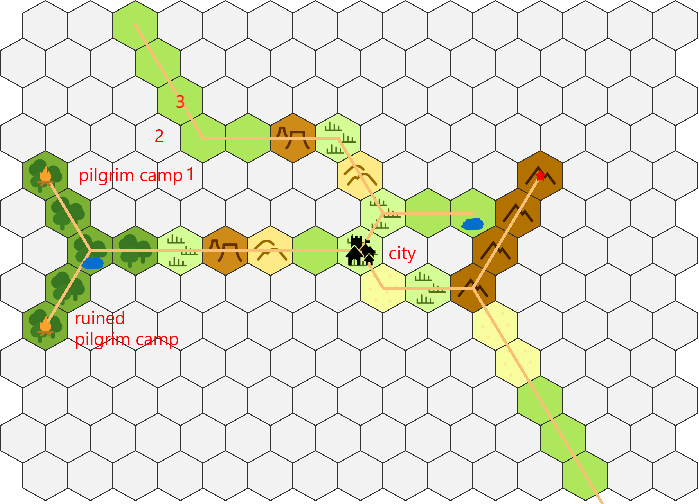

Alternatively, you can use a procedural generator that simultaneously creates terrain and roads. Martin Ralya’s Hexmancer offers one of the better attempts at this approach. While Ralya credits Jedo of the New York Red Box forums for inspiring Hexmancer, their system’s chassis is essentially Appendix B coupled with a method for generating roads and rivers. Hexmancer generates roads and rivers as follows: “roll a d5 and count clockwise from the point of origin (the hex side they’re leaving). That’s the side where feature exits the new hex.” While this makes fairly natural rivers, the roads inevitably tend toward illogical at best to nonfunctional at worst (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Example of roads generated by Hexmancer

I have attempted to use Hexmancer dozens of times to create sensible roads, but they all trend toward the example in figure 2. As my example illustrates, Hexmancer’s system often results in switchbacks. For instance, in the easternmost badlands hex, the road heads southwest to the hills. If you were following this road to its final destination in the plains hex, why would you ever stay on it? Why not simply cut across the badlands to the forest? Or in the northernmost plains, why not cut across to the badlands? (Perhaps you need something in one of the castles?) Of course, one could explain these switchbacks by saying that these are sheer cliffs. While there are arguments to be made for gamifying the edges of hexes, I find that’s a level of detail I’m unlikely to remember when I’m procedurally generating a map.

Note: While creating the map above, I tweaked Hexmancer’s rules a little bit based on an extrapolation of his instructions. When determining which direction a road travels, I rolled a die equal to the number of open hexes. Thus, if there are four uncharted hexes, I rolled a d4 instead of a d5. Otherwise, the road can quickly become a closed loop—and that doesn’t make sense to me. Even Ralya concedes that “You may need to apply a bit of logic, or tweak the results, in order to make byways and waterways fit the map.”

What if we didn’t need to worry about tweaking the results? What if a procedural generation system could create logical routes even when we don’t know where they are going? For months, I thought it was impossible. I think I solved it though.

Method

For sake of clarity, the following method only describes how to create roads and landmarks. When I tested this method, I also used Appendix B from AD&D’s DMG (fig. 1) to generate terrain. When I run a solo campaign with it, I intend to use my own homebrew exploration rules (such as for tracking travel, charting neighboring hexes, becoming lost, and determining encounters). I believe my method for creating roads can be easily integrated with any other systems. Please use whatever exploration rules work best for you.

(I have also included an appendix with sample maps generated by this method, as well as a step-by-step demonstration with images, to serve as a reference.)

- Identify a hex to start in and roll a d8 to determine its terrain.

- Roll a d3 to determine the habitation of the starting hex:

- 1 – Thorp (20-80 pop)

- 2 – Village (600-900 pop)

- 3 – City (10,000-60,000 pop)

- Roll a d6 to determine road placement. Roads travel through the center point of each hex, not along hex boundaries. Starting from the top of the starting hex, count clockwise that many sides:

- Thorp: 1 road on the indicated side.

- Village: 2 roads – one on the indicated side, one directly opposite.

- City: 3 roads – one on the indicated side and the other two on alternating sides clockwise from it.

- Note: When establishing a road in the starting hex, extend it straight-ahead into the middle of the next hex before proceeding to step four. (This allows for the possibility of a fork in the road near the starting hex.)

- Roll 2d3 (using different colored die).** Establish one color as the direction, and the other as the distance.

- If both d3 show the same result, create a fork in the road. Of the three possible directions, use the two that are furthest apart and travel the distance rolled.

- Rolling doubles twice in a row immediately results in both roads ending with a destination. Do not extend either road beyond the first double. Instead, roll a d10 on Table 1 to determine the landmark at each dead end. (The chance of rolling two doubles in a row is 1/9, or 11.11%, thus landmarks are fairly common.)

- Repeat step 4 until the road ends or exceeds the limits of your hex paper.

Exceptions:

- A road cannot turn the same direction three times in a row (regardless of how many straight-ahead moves each stretch of road might include). On the third turn, it must turn the opposite way. If this third turn is caused by a fork, ignore the branch that would create the third consecutive turn in the same direction.

- Only one fork is allowed among the six hexes adjacent to the starting hex. If another fork is rolled, treat it as a direction 2 result and move the distance rolled instead.

- A new road entering a hex with an existing road must stop and form a fork, regardless of any remaining distance rolled.

**If you do not have 2d3, you could roll 2d6 instead. Treat 1-2 as “1,” 3-4 as “2,” and 5-6 as “3.” Thus, if you roll a 1 and 2, that would be a 1 for direction and 1 for distance resulting in a fork in the road.

| d10 | 1 Space from Fork | 2 Spaces from Fork | 3 Spaces from Fork |

| 1 | Thorp | Village | City |

| 2 | Bandit camp | Coven | Outpost |

| 3 | Cave | Mine | Lair |

| 4 | Shrine | Pilgrim Camp | Remote Monastery |

| 5 | Hut | Manor | Castle |

| 6 | Tomb | Dungeon | Wizards Tower |

| 7 | Nothing | Nothing | Nothing |

| 8 | Ruined result of 4 (Shrine) | Ruined 4 | Ruined 4 |

| 9 | Nothing | Nothing | Nothing |

| 10 | Ruined result of 5 (Hut) | Ruined 5 | Ruined 5 |

Table 1. Landmarks

While the landmarks table allows for the placement of another city, you should not extend three roads from it as you would for a starting city. This would create two forks in a row, which my method prohibits. Instead, extend a single road directly through it like a village (it remains a city, however).

Note: The landmarks table is something I whipped up to test this road generator. For each category I tried to create something that was progressively larger or more challenging the further away it extended from a fork. For instance, hut –> manor –> castle. Since I still intend to generate landmarks on other hexes using my own hex crawling rules, I made two d10 results (7 and 9) generate nothing. That might be a mistake, but I like the possibility that a road might lead to a landmark that no longer exists (any ruins are too scant to count as a landmark). Alternatively, the road could be in the process of being built. Speaking of which, I also experimented with having a 7 or 9 result in the path continuing further. I stopped doing that, however, because I felt like it caused more roads to connect. Perhaps it would be fine if only one of these options (7 or 9) extended the path.

Parting Thoughts

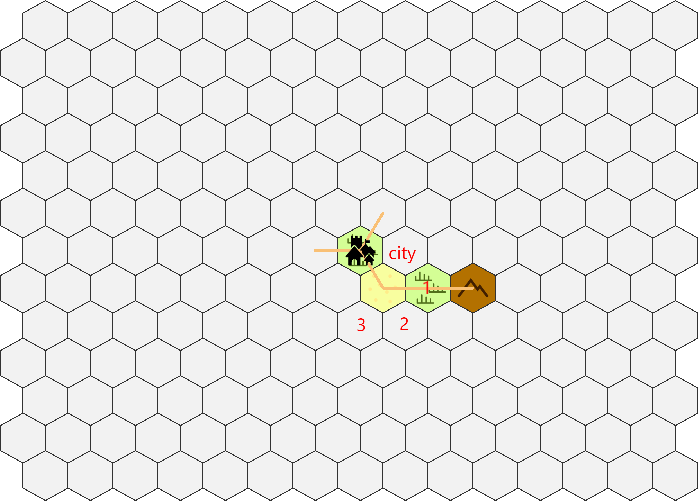

On the whole, I am very happy with this method. As I mentioned at the start, this technique creates roads that feel meaningful and lead to interesting destinations. It’s also relatively straightforward and consistent. As with any procedural generation, it can sometimes lead to wonky results, but these are few and far between as far as roads go. Sometimes a fork in the road will create alternate paths to the same destination (see fig. 5). I don’t consider that a problem however. Often the terrain varies so much that one can make a plausible explanation for one might prefer one route at any given moment. For instance, in fig. 5, my exploration method gives a benefit to those who chart on mountains—they get to see twice as far owing to the elevation—though the western route via the desert hexes would result in a faster trip south.

That said, there are at least three potential downsides to this method. First, if you lack d3 dice or 2d3 of different colors, I’m sure this method could become mentally taxing. Thus, not having the right dice could be a considerable hurdle for implementation. Second, I think this method works best for relatively small hexcrawls. I mostly used a hexmap spanning 13×15 hexes to test this method. I also tested it a few times on a hexmap spanning 23×28 hexes, but I was less satisfied with the results. When you have more hexes to chart, the possibility of disparate roads connecting seems to increase. I don’t think this is necessarily a problem, however, as I believe that people generally use smaller hex maps. Third, by allowing three roads to extend from a city, you dramatically increase the possibility of having roads converge. I debated reducing the city to only two roads extending from it, but I like the idea of a larger population having more roads. Moreover, while the likelihood of having roads converge increased, it was never guaranteed.

At this point I have generated over 30 maps using this technique. I encourage you to try it and let me know how it works for you.

Appendix

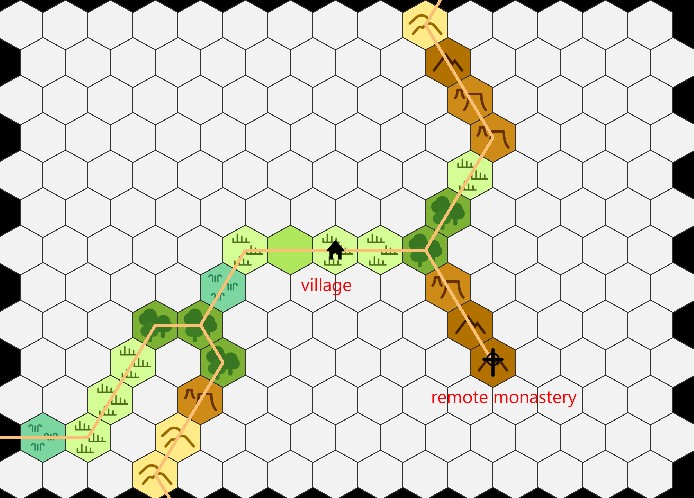

The following figures are examples of different starting locations (thorp, village, and city). I have left the rest of the terrain blank to improve clarity.

Figure 3. Thorp

Figure 4. Village

Figure 5. City

Demonstration

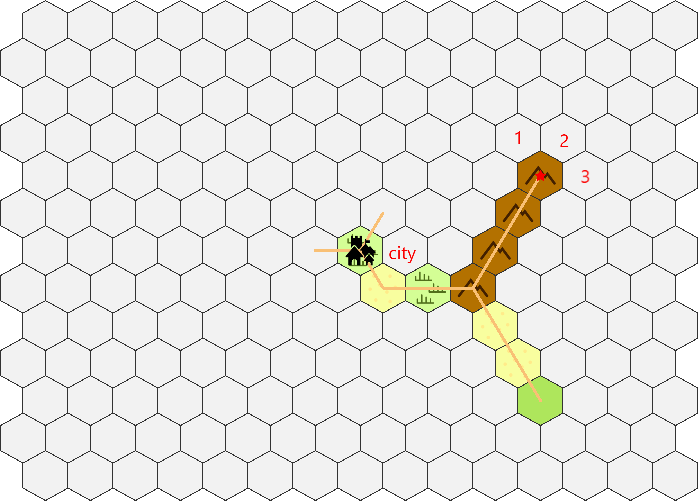

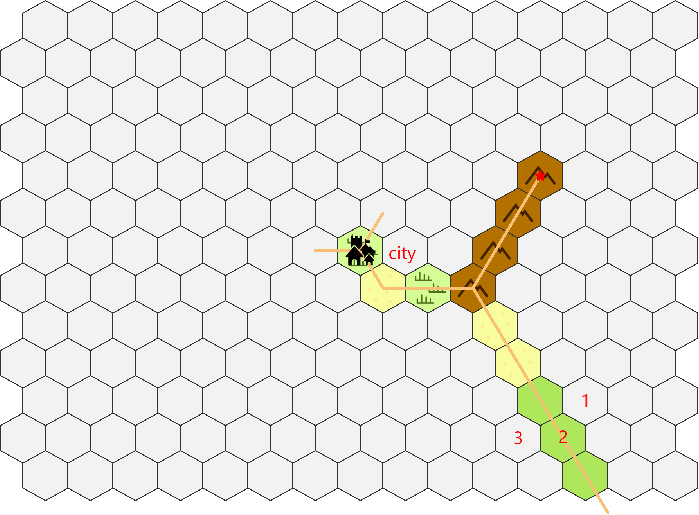

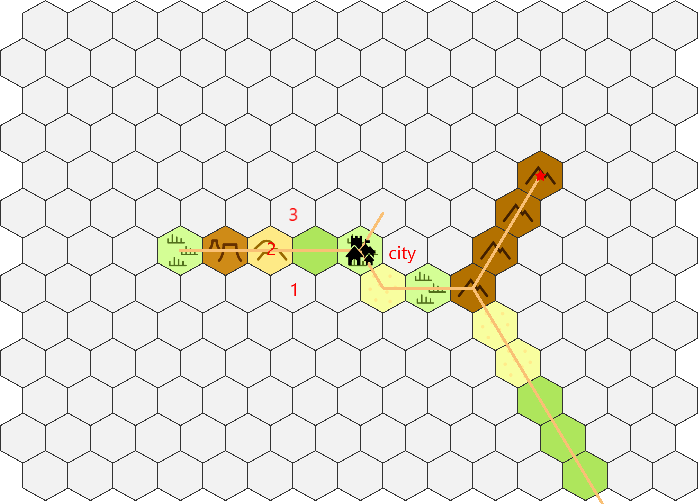

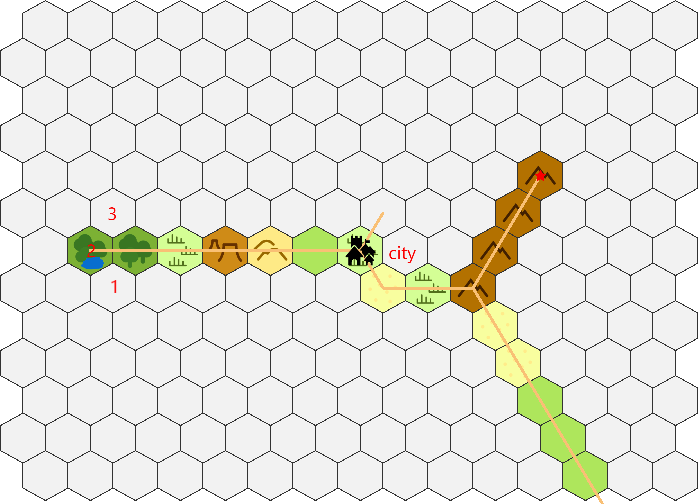

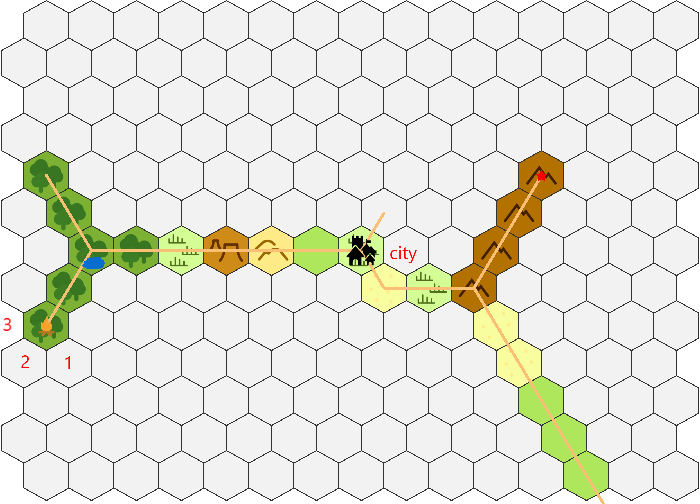

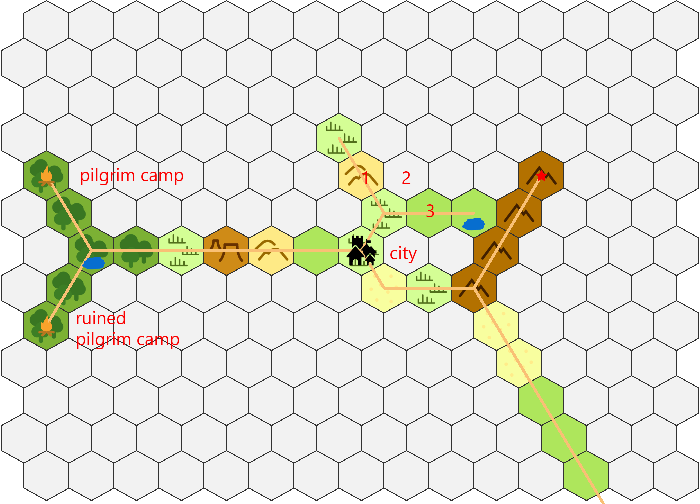

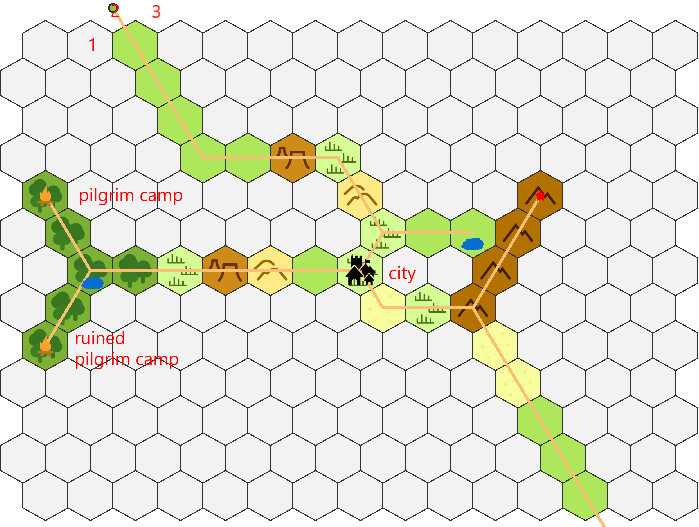

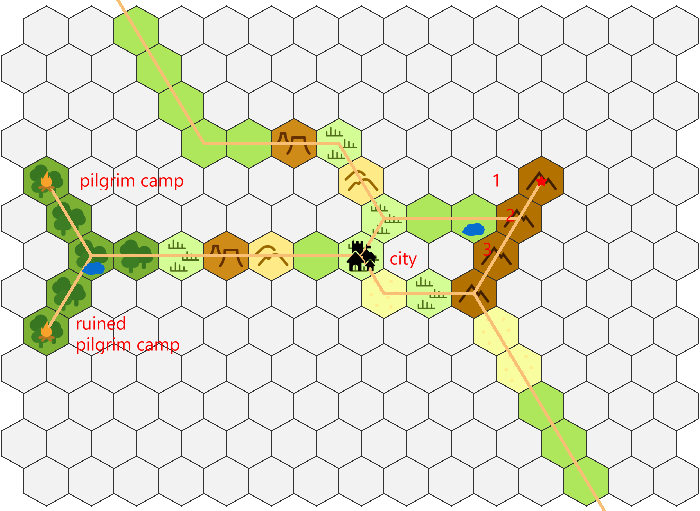

The following is a step-by-step example of my method for creating roads.

Habitation creation

- d8: 2 (scrub); d6: 3 (SE); d3: 3 (city)

First road

- Roll 1: 1 for direction, 2 for distance.

- Roll 2: 3 for direction, 3 for distance (fork).

Roll 3: 1 for direction, 1 for distance. Since it’s the second fork in a row, I establish a landmark. I rolled 7, meaning nothing is here and road ends.

- Roll 4: 2 for direction, 3 for distance.

Second road:

- Roll 1: 2 for direction, 3 for distance.

- Roll 2: 2 for direction, 1 for distance.

Roll 3: 2 for direction, 1 for distance.

- Roll 4: 2 for direction, 2 for distance (fork).

- Roll 5: 1 for direction, 1 for distance. Since it’s the second fork in a row, I establish a landmark. I rolled 8, resulting in a ruined pilgrim camp. (I forgot to label it until starting the third road.)

- Roll 6: 2 for direction, 2 for distance. Since it’s the second fork in a row, I establish a landmark. I rolled 4, resulting in a pilgrim camp. (I forgot to label it until starting the third road.)

Third road:

- Roll 1: 2 for direction, 2 for distance (fork).

- Roll 2: 1 for direction, 3 for distance.

- Roll 3: 1 for direction, 3 for distance. (This would be the third counter clock-wise turn in this road, thus instead of heading toward 1 it will go toward 3 instead.)

Roll 4: 2 for direction, 1 for distance.

- Roll 5: 2 for direction, 3 for distance. (This road extends into a previously established road. Although that hex is only 1 away and I rolled 3 for distance, the new road cannot cross over the previously existing road.)

Leave a comment