In my previous post, I highlighted rules I homebrewed for hexcrawls. Apart from a desire to tinker with game design, I wanted to offer my players a means of making meaningful travel choices without showing them the complete map. To reveal the map, players need to contend with a fog of war mechanic, which they can push back by traveling and charting the landscape. Both of these mechanics, traveling and charting, take time and the amount of time is dictated by terrain type. Some terrain, such as forests, are easier to travel through than chart. While other terrain, such as mountains, are easier to chart than travel.

One of the primary benefits of fog of war is that it provides players with more agency. Nonetheless, players often explore the map slowly (if only because of its size) or because they rely heavily upon previously trodden paths. Sachagoat explores the latter phenomenon in part 1 of their series, “Re-inventing the Wilderness.”

To help overcome this obstacle, I created two additional methods for exploring hexmaps: pay the merchant guild to disclose hexmap information OR play as a cartographer. Both of these methods differ significantly in their level of complexity. The first method immediately provides groups with information about the hexmap. The second method caters better to solo play and offers information that will be useful for future sessions.

Pay the Merchant Guild

Players may immediately remove the fog of war by paying gold. Doing so reveals the terrain type(s), as well as any landmarks contained therein. There are three caveats, however:

- Players must be in town to do so, as they are receiving this knowledge from the local merchant guild.

- Players can only use this method on hexes that have a road running through them.

- These roads must originate from the central city.

The cost for revealing hexes grows cumulatively by increments of 5 gold pieces. The first hex costs 5 to reveal, the second hex costs 10, the third costs 15, and so on. Thus, revealing the first three hexes would cost 30 GP (5+10+15). If players previously explored several hexes along the road and use this method to see what lies beyond, they may do so by counting the number of hexes the road runs through and paying the value of the unknown tiles. For instance, if the known route ends at nine hexes, the tenth hex would cost 50 GP, the eleventh 55 GP.

Play as a Cartographer

A player may also pay a cartographer to map the surrounding countryside on their next excursion from the city. Unlike paying the merchant guild, wherein results are immediate, this approach may take an entire session as a player controls an NPC in lieu of their own character(s). Since cartographers may roam anywhere on the hexmap, they can reveal hexes without roads running through them.

I introduced this option during a session in which only one player could attend. Effectively, it allowed her to continue playing without endangering any of her characters. While she could have completed one of the available quest hooks with hirelings, this option allowed her to flesh out the hexmap for future sessions by attempting to track down the location of rumored landmarks. (Although playing as a cartographer was designed for solo-play, I could envision a session in which two or three players simultaneously send out their own cartographer in different directions.)

Playing as a cartographer was inspired by Daniel Norton’s YouTube channel, Bandit’s Keep Actual Play. Since January 2023, Daniel has run an ongoing Original D&D solo campaign on the Outdoor Survival map. One of Daniel’s innovations is playing as a mapper using OD&D’s wilderness rules combined with Outdoor Survival’s movement rules. Each turn Daniel rolls to determine whether his mapper is lost before deciding which way to navigate the hex map. If the mapper becomes lost, they must move one hex in a random direction before proceeding toward their destination. The turn ends by rolling for a random encounter. You can watch this in practice here.

In Daniel’s solo campaign, the mapper is a slight misnomer as they are not creating a map, but rather retrieving them. His mapper only maps when they identify a monster’s lair. For my campaign, however, the primary purpose of the cartographer is to push back the fog of war and reveal locations of interest. In short, they create a map. As such, while I maintain Daniel’s emphasis on the tensions of becoming lost and having encounters, I have made a few key changes to make a cartographer work in my campaign. Namely, a player must create a contract with a cartographer to predetermine how long they spend mapping. Moreover, the cartographer explores the map through turn-based travel. Each turn lasts one week, including a day of rest on the seventh day.

To play as a cartographer, a player needs to decide how many weeks they are willing to fund a mapping expedition before the cartographer leaves town. Each week of mapping costs 10GP. Any number of weeks is permissible, provided players pay the entire sum upfront. At the end of this agreed upon period, the cartographer will send a map back to town via passenger pigeon. Since a player’s primary character does not join the cartographer, they cannot use any information revealed on this trip until the expedition ends. Thus, even if a player can afford a longer expedition, they may want to keep the expedition relatively short. (Alternatively, they can pay extra for the cartographer to relay a pigeon once a month or when a specific condition is met, such as locating a specific landmark. Pigeons are limited, however, and each one costs an additional 25GP. I have never had a player attempt to send a pigeon back every week, but if they did, I would make each subsequent pigeon more expensive.)

Once the player decides the length of their contract, the DM secretly determines when encounters may occur. Encounters can only occur Monday through Saturday. To determine when an encounter may occur, the DM makes a hidden d6 roll for each individual week and records the result (1 for Monday, 2 for Tuesday, and so on). When this day arrives, the player makes an encounter check to see whether there is an encounter. The likelihood of having an encounter depends on the terrain they enter that day (see addendum).

Cartographers use the traveling and charting mechanics from my last post to push back the fog of war, as well as discover landmarks. Each turn, the cartographer may use any combination of travel and charting provided it does not exceed six days. For instance, they can travel through three forest hexes; OR they can travel through a plain, hill, hill, while charting in any of those hexes; OR they can enter one mountain hex. If a cartographer attempts to move into a hex that takes more days than they have remaining for that week, explain that they cannot afford to move into that space without disclosing the terrain type. (The only time I disclose the terrain type is if the entire hex is a body of water that makes travel impossible.) If the cartographer is unable to travel or chart without exceeding six days, they spend the rest of that week resting. If a potential encounter was scheduled for an early resting day, such as a Friday or Saturday, the player still makes an encounter check at their current location on that day.

In Daniel’s playthrough, if a mapper does not make it to a safe haven within seven days, they perish. While this can be a fun challenge using the Outdoor Survival map, fog of war makes this impossible. As a result, a cartographer does not die in my game. Having an inefficient cartographer is enough of a penalty in my campaign.

When the cartographer’s contract is complete, they send a passenger pigeon back to town with the map. This pigeon returns on the Sunday of their last week of mapping. Since this pigeon effectively provides players future knowledge in the present, this may pose some challenges as players now have knowledge that their characters do not have yet. There are a few ways of dealing with this. If players want to pursue a new lead provided by the cartographer, the DM should simply move the timeline forward to the day the pigeon returned. Alternatively, if the players intend to follow up on something else first, there is no need to move the timeline. Often my players will send a cartographer in the opposite direction of their current exploits. And indeed, the value of a cartographer is precisely found in their ability to let players effectively explore two directions at once.

Since playing as a cartographer is well suited for one player at a time, a DM may also have a player create a separate map when paying a cartographer. After all, the player’s character is paying for this knowledge—not the whole party. This way, anyone else playing in the campaign can continue to explore the map without their timeline being constrained by another player’s choices.

Conclusion

In this post, I suggested specific prices for knowledge from the merchant guild or a cartographer. While I have found these prices to be reasonable in my campaign, I realize that no two campaigns share the exact same economy. As such, DMs should feel free to adjust these prices to fit their own campaign. Generally speaking, a cartographer should be cheaper than paying the merchant guild, but not so cheap that players would much rather send out cartographers than sally forth with their own characters. Both techniques are meant to inspire the party and help them discover new quests or places of interest.

Both of these mechanics work nice in tandem because they have different strengths and drawbacks. Paying the merchant guild to reveal hexes works immediately, unlike venturing out into the wilderness. Since paying the merchant guild requires players to be in town, it can be utilized either at the start of the session or the end (again, assuming one is playing a West Marches campaign). This allows players to make a more informed decision when preparing to follow up on particular quest hooks, while also adhering to a fog of war mechanic. Although paying the merchant guild is more expensive, time is money and even a substantial sum could be recouped long before a cartographer completes their contract. Speaking of which, paying the merchant guild can also offer a practical gold sink for players. This is an especially important feature for my campaign since I use Dungeon Crawl Classics. Official DCC modules often distribute lots of wealth to players, but offer few opportunities to spend it.

One of the primary drawbacks to the paying the merchant guild is that you can only reveal hexes with roads extending from the starting city. Hiring a cartographer allows players to roam in a less constricted manner. There is a slight gamble to the enterprise, however. A cartographer is generally cheaper than the merchant guild, but the usefulness of a cartographer largely depends on luck. If the cartographer consistently becomes lost or finds themselves in challenging terrain, they might not reveal much of value. Encountering monsters may also result in a shorter trip overall. Beyond poor luck, the main drawback of the cartographer is that this exploration is not immediate. The player’s characters cannot act on this knowledge until (one of) the cartographer’s passenger pigeons return to town. The severity of this drawback depends on the type of campaign you run. If there are multiple groups of players exploring a hexmap independently of each other with their typical characters, it’s possible to pay for out-of-date information. For instance, a player may learn where a dungeon is, but in the meantime another group could successfully discover and explore it on their own while roaming the map.

Addendum: Clarification on Becoming Lost/Encounters

Initially, today’s post contained the following material within the section on the cartographer. It became quickly apparent, however, that doing so was making my explanation too convoluted. In an effort to promote clarity, I have moved my description of how a cartographer becomes lost or has an encounter into this addendum. My methods for either are not essential to how the cartographer functions. I simply explain them so that others can better understand how I handle either outcome. DMs are more than welcome to use their own methods. And so, without further ado, here’s my methodology:

Each week brings the possibility of becoming lost or having an encounter. For both options I draw upon OD&D’s Volume 3, in which terrain type dictates the probability of becoming lost or encountering a monster. Since I created my hexmap using AD&D’s DMG, I needed to revise these numbers to account for additional terrain types, such as badlands and scrub. Thus, in my campaign, a cartographer becomes lost or has an encounter on the following results of a d6 roll:

Plain

Lost: 1

Encounter: 1

Scrub

Lost: 1-2

Encounter: 1-2

Marsh

Lost: 1-3

Encounter: 1-3

Desert

Lost: 1-3

Encounter: 1-2

Forest

Lost: 1-3

Encounter: 1-2

Hill

Lost: 1-2

Encounter: 1-2

Badland

Lost: 1-2

Encounter: 1-2

Mountain

Lost: 1-2

Encounter: 1-3

Becoming Lost

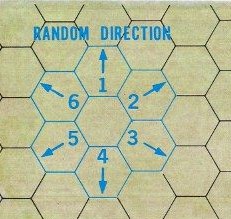

Players determine whether the cartographer is lost at the start of each week, except for when they first leave town. To do so, roll a d6 and consult the numbers above. If the cartographer is lost, they must immediately move into a randomly selected adjacent hex. To determine which direction they move, roll a d6 and follow that orientation on the compass rose (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Compass rose from Outdoor Survival

Aside from potentially wasting time moving in the wrong direction, becoming lost carries two other penalties. First, if the cartographer moves into a hex with a road, they are unable to find it. Thus, the cartographer cannot take advantage of a road’s ability to cut travel time in half (I discuss this feature in my last post). If the cartographer subsequently moves into another hex with a road, they are presumed to have found the path again and may reduce their travel time. Second, whenever the cartographer is lost, they cannot chart surrounding hexes until they move into a new hex.

Players may start their turn by charting the surrounding terrain, but they need to make this decision before rolling to determine whether they are lost. Players may also become lost in any hex, regardless of whether they have explored it previously.

Encounters

In OD&D, encounters are chance meetings with monsters that almost always result in fighting or fleeing. As several OSR blogs have noted, this approach to encounter design is fairly limiting and frankly uninspired. (See Prismatic Wasteland’s post, “Hexcrawl Checklist: Part Two,” for a good summary of other bloggers and links to their respective articles.)

In my current campaign I have modeled encounters after another one of Daniel Norton’s videos, “Exploration with Hexcrawls.” Essentially, Daniel rolls 3d8 at the start of a new day to generate encounters from an assortment of tables including monsters, trap/hazard, special, signs of destruction, weather event, location, and pilgrims. He then deftly creates a coherent explanation for how these disparate results may work together for his players on that day. Doing so places a greater emphasis on creating a narrative than random monster melees.

For my purposes, weaving together three separate encounters each day is a bit too much. Instead, I opt for rolling a 1d8 each week while using a modified version of his encounter tables. The options I use for the cartographer are:

1-4

5-6

7

8

Monster

Hazard

Location

Surreal Occurrence

These types of encounters offer potential challenges to encountering the wilderness, while also generating future plot hooks.

Monster

Monster encounters are a source of narrative richness and literal riches. Not every monster encounter needs to include a wandering monster, however. A player, for instance, may stumble upon a monster’s lair or footprints. A lair serves as a mini-dungeon and thus always guarantees some degree of loot should a party subsequently explore it. Tracks, however, are simply suggestive for future plot hooks. For instance, if the party is looking for centaurs and the cartographer stumbles upon centaur tracks, the party may now know their general whereabouts.

Whenever there is a monster encounter, I first determine the type of monster by consulting a terrain-based encounter table. Then, following Daniel’s model, I roll a d6 to determine whether the cartographer encounters a wandering monster (1-2), it’s lair (3-4), or footprints (5-6).

When a cartographer encounters a wandering monster, they must attempt evasion. The number of monsters encountered is immaterial for a cartographer since they will always attempt to flee. They can never fight or persuade wandering monsters. The cartographer has the exact same chance of evading—or rather, losing—a monster as they have becoming lost in a specific terrain type. For example, since a cartographer becomes lost if a 1 is rolled on a plain hex, they also need a 1 to evade monsters in a plain.

If the cartographer evades a wandering monster, they remain at their current location. The monster can be described as spooked or losing sight of the cartographer. If the cartographer is unsuccessful, they must flee in a random direction by rolling a d6 as though they are lost. Fleeing costs the cartographer one week of travel because they drop a week’s worth of supplies to distract the monster and guarantee their escape. If the cartographer is unable to afford to move in that direction (for instance, perhaps they only have two days of movement left and they are surrounded by forests and mountains), they remain where they are, and drop another week’s worth of supplies to appease the monster. This concludes their current turn/week.

Each time the cartographer drops supplies while fleeing a monster, they reduce their total trip by a week. DMs should simply ignore the last agreed upon week(s) of travel when tracking potential encounters. If the encounter happens during their last agreed upon week of travel, they send the pigeon immediately with an earnest plea to the party to tell their family that they love them and that they should not cry. This can become its own plot hook.

Hazard

Hazards are moments where forward progression is either stalled, impeded completely, or redirected randomly. For instance, the cartographer may find their progress slowed by quicksand. Alternatively, the cartographer may encounter an object like an avalanche that forces them to backtrack. Fog may result in another check to see if the cartographer is lost, albeit midweek. I encourage DMs to use hazards in a way that builds upon clumps of similar terrain. For instance, perhaps the cartographer needs to go around an entire forest to avoid a forest fire.

Location

Location encounters are places for the cartographer to make note of and the party to follow up on. Daniel uses ancient empty ruins, ruins, temples, and special locations. For my campaign, I already generated these types of objects when I created my hexmap, but using the cartographer to create more makes the game more dynamic for myself. Not everything needs to be for the player roleplaying as the cartographer. The DM is a player, too.

Surreal Occurrence

When constructing my surreal occurrences table, I selected 20 options from Bradley K. McDevitt’s “A D50’s Worth of Surreal Occurrences” from Goodman Games’ 50 Fantastic Functions for the D50. I chose options that created a sense of wonder without requiring immediate combat. For instance,

“Cold Snap: at the height of summer, the PC’s awaken to find a rime of frost on their gear and all around their camp. Investigating, they find the bodies of several small woodland animals nearby, flash frozen” (100).

And

“The Crater: the PC’s arrive at a crater, several yards across. Even though the ground is still hot, and rocks exposed by the impact are still smoking and red-orange with heat, at the center of the depression is a giant skull, still so cold that touching it raises blisters when touched” (101).

The potential choices are meant to raise more questions than answers and make the players either fearful or desirous to explore that region. As with all the encounters, surreal occurrences are meant to help the world become even more alive.

Leave a comment